Between the age of six to eight, my older brother and I would stay up late during the summer and watch classic movies which would play every weekend on CBC (Canadian Broadcasting Center). This was around the time I became obsessed with the idea of one day becoming a filmmaker. We’d watch films such as The Beguiled, starring Clint Eastwood, West Side Story, Rebel Without a Cause, Deliverance (which we shouldn’t have been watching at this age, fucked up movie), The Graduate and countless others.

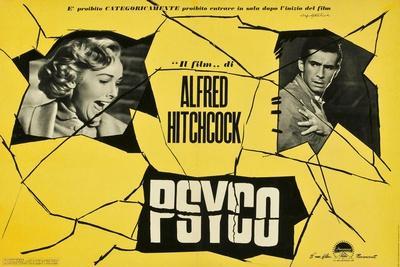

At some point in late July, as the sweat poured within the boiling hot bedroom while watching film after film, the movies of Alfred Hitchcock began to play, starting with Dial M for Murder. I wasn’t a big fan of Dial M, but The Birds, Rear Window and North by Northwest became early favorites. One aspect of Hitchcock’s films I had taken note of was the exceptional film scores. This was, to be entirely honest, before I knew what a film score was. It was all music to my ears. A substantial amount of the scores to Hitchcock’s films were evidently composed by Bernard Herrmann. Bernard’s film scores were notable in building an intricate layer of suspense to Hitchcock’s films. This was most notable in my favorite film directed by Hitchcock, Psycho.

For any cinephiles unaware, Psycho told the story of a sexy secretary, Marion Crane, played by the beautiful Janet Leigh, who steals $40,000 from her employer, in an ill-fated plan to run away with her boyfriend, Sam Loomis. Along the way, she buys a new car and remains on the grids to avoid to cops. Exhaustion brought on by anxiety in relation to the theft, along with a steady rainstorm, leads Marion to take refuge at a creepy motel in the middle of nowhere. Upon entering the motel, Marion is greeted by the awkward and nervous mannered motel proprietor Norman Bates, played by Anthony Perkins, who lectures Marion on his passion for taxidermy, as well as his love for his mother which borders on incestuous. Norman indicates a childlike attraction to Marion as they share a coffee, and books her a room. Meanwhile, Norman has a heated conversation moments later with his overbearing mother. However, his mother remains unseen during the heated exchange.

Upon entering her hotel room, Marion, exhausted, hides the stolen cash within a newspaper and prepares to shower. As she undresses, Norman spies on her through a hole in the wall from within his taxidermy trophy room. And a moment later, Marion is seemingly stabbed to death by Norman’s mother as she showers, or was it really his mother after all...

Now the film itself through Hitchcock’s impeccable direction was already high on tension, but Bernard Herrmann’s score intensified the suspense to another level yet to be witnessed or heard by movie goers to that point. This was 1960 after all. When sexuality in films was based more on innuendos and when violence didn’t contain hyper-realism as it does today.

The novel Psycho was written by Robert Bloch, who had based the character of Norman Bates on real life serial killer, Ed Gein. Gein had killed two women in Plainfield, Wisconsin during the fifties and was suspected of committing upwards of seven additional murders, through the hope of creating a “woman suit” so that he could quite literally become his mother following her death. For those who have watched Psycho in its entirety, which I don’t intend on spoiling, then this will all sound very familiar.

Hitchcock had received a reduced budget for the film adaptation of the novel, and had even financed the film himself, proposing a 60% stake in the film negative, which would later become one of the best financial decisions he could have made. Despite the low budget of the film, Bernard Herrmann was adamant not to receive a reduced fee for the film’s score. Hitchcock agreed to this, and Hermann wrote and conducted the film score, which Hitchcock believed elevated the tension to new heights. With this assertion, I can’t help but agree. Take the car sequences, for example, as Marion drives following the theft of the money, alone with her thoughts. Had her frantic inner dialogue been the only thing heard by the audience, and had Herrmann’s film score not been playing simultaneous to the voice over, would the tension have built the same as it had? Likely not.

Also, throughout the shower sequence, as Marion is murdered, the piercing notes heard throughout the score by Herrmann feel like deep cuts of a blade. We felt Marion’s pain, her panic, despite the actual scene itself not being overtly violent. It didn’t have to be. Hitchcock, through his expert direction and meticulous storyboarding, along with a score which remains among the most notable of classic Hollywood, why would there be a need for unnecessary violence?

Films of the early forties through to the mid sixties, before a counter-culture hit in the late sixties which flipped filmmaking on its axis, had to depend highly on the story, screenplay, and acting. Before technical aspects in filmmaking improved, such as special effects, which has since become a cheap substitution for a strong story, having a superior film score also attributed to how the film was perceived by audiences. In the case of Psycho, audiences were consumed with uncontrollable fear. They had, quite simply, never seen anything like it before.

Take this for example; in 1931, Bela Legusi had starred in a film adaptation of Dracula. The film was based on the novel of the same name, written by Bram Stoker, in 1897. Dracula, in essence, was the equivalent of an urban legend, or in this case, film monster in the eyes of audiences. A vampire sucking the blood of unsuspecting victims in order to survive? Talk about farfetched! The concept of a Dracula, or a Frankenstein, left the audience with a false sense of security. Monsters aren’t real, they only exist in the movies! Then along comes Psycho, which demolished the previously misguided assumption that monster’s were only real in the movies, when rather, the real monsters could be found through the slightly off smile of the friendly neighbor, or in this case, the seemingly innocent motel proprietor. This previously ignored reality evidently changed the very fabric of filmmaking forever. Horror movies contained real people as the villain and dealt highly on psychological aspects in relation to the human condition. Psychological warfare, manipulation, seduction, and coercion became common character traits held by the antagonist, as the protagonist struggled to solve the tangled web spun before them, before they too became an unsuspecting victim.

In the years which followed Psycho, the nature of criminality behind serial killers also caused these ghastly crimes and exploits to become fixtures of the nightly news, in the United States especially. As the world struggled to grasp the motives behind these evil, deplorable individuals, in late sixties high profile cases such as the Zodiak Killer or The Manson Murders especially, the nature of filmmaking continued to morph into what it is today. Where a stomach churning Netflix show based on the horrendous crimes of Jefferey Dahmer was able to eventually see the light of day. So in essence, Psycho became one of the first films to have taken inspiration from real life crimes and apply them to a fictional world, forever changing the landscape of filmmaking.

Janet Leigh developed a life-long fear of showers following the making of the film, deciding instead to take baths for the remainder of her life. Her eventual ex-husband Tony Curtis, portrayed real life suspected serial killer Albert DeSalvo in the 1968 film, The Boston Strangler. And in 1978, Janet’s daughter, Jamie Lee Curtis, played Laurie Strode in the John Carpenter directed, Halloween. A performance which catapulted Jamie into stardom, which may have played an eventual role in her winning a supporting actress Oscar for her performance in Everything Everywhere All At Once just last month in March of 2023.

Upon first viewing of Psycho, my perception of what was possible through filmmaking had forever changed. In the years which followed, I have given the film repeat viewings and have arrived at the conclusion that the score turned the film into a horror masterpiece. The same could be said in regards to Krzysztof Penderecki’s film score of Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining, which may be featured within a future blog post.

The desire to aspire for a career in film was heavily attributed to Psycho. Although this dream has yet to became a reality, it did ultimately lead me on a course to open an online record store, which also features sales items related to pop culture. For anyone who has yet to watch the film, it is highly recommended. As well as many of the other films within the master of suspense, Alfred Hitchcock’s, legendary filmography.